[ad_1]

When the U.S. debt-ceiling fight finally is resolved, the Treasury is expected to unleash a flood of bill issuance to help refill its coffers run low by the protracted standoff in Washington, D.C., over the government’s borrowing limit.

The question is, who will buy them and at what price?

Treasury bills are debt issued by the U.S. government that mature in four to 52 weeks. New bill issuance could reach about $1.4 trillion through the end of 2023, with roughly $1 trillion flooding the market before the end of August, according to an estimate from BofA Global strategists.

They expect the deluge through August to be about five times the supply of an average three-month stretch in years before the pandemic.

“The good news is that we have a high degree of confidence around who is going to buy it,” said Mark Cabana, rates strategist at BofA Global, in a phone interview with MarketWatch. “The bad news is that it’s not going to be at current levels. Things have to cheapen.”

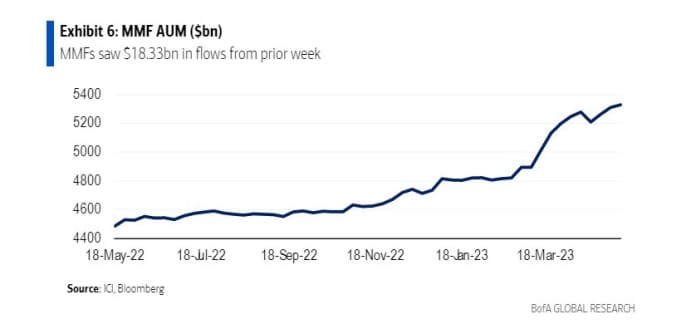

Cabana sees a key buyer of bill supply unleashed by a debt-ceiling deal in money-market funds, which have climbed to nearly $5.4 trillion in assets managed since the regional banking crisis erupted in March (see chart).

So people who yanked billions of dollars in deposits from banks after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March and parked them in money-market funds could end up playing an encore performance in this year’s debt-ceiling drama.

Money-market funds swell since March, topping $5 trillion in assets

BofA Global

Related: Money-market funds swell to record $5.4 trillion as savers pull money from bank deposits

$2 trillion at Fed repo facility

Money-market funds have been the main reason why at least $2 trillion consistently sits overnight at the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo facility. The program was last offering a roughly 5% rate, a level Cabana said new Treasury bills might need to exceed by about 10-20 basis points.

“It’s an unintended consequence of a debt-ceiling deal getting done,” said George Catrambone, head of fixed income Americas at DWS Group, about market expectations for heavy short-term Treasury bill issuance, but he also expects money-market funds, foreign buyers and other institutions auctions to continue as buyers in the market.

“There’s always buyers. It’s a question of price.”

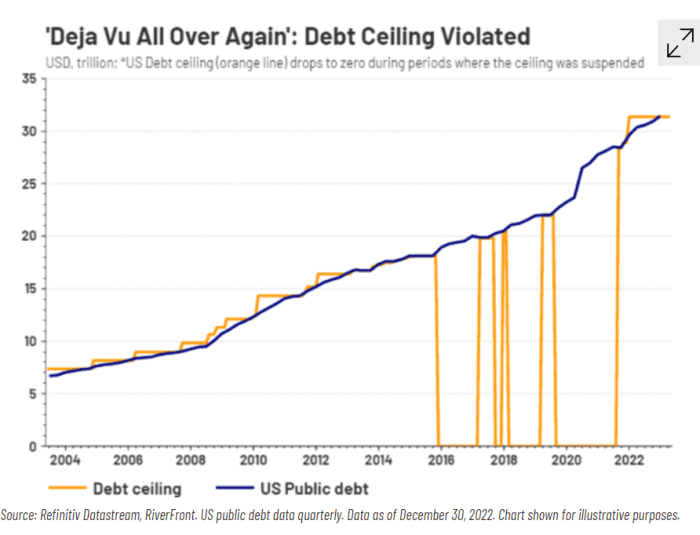

President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif. met Monday to talk about potential ways to raise the $31.4 trillion borrowing limit and to avoid a “doomsday” scenario in financial markets if the U.S. defaults.

Congress has struck deals each time U.S. public debt has exceeded its debt ceiling in the past, including by suspending it eight times since 2016 (see chart).

In the past when the U.S. debt-limit has been violated, Congress extended or suspended it

Refinitive, RiverFront

That doesn’t mean financial markets sit by idly. The 1-month Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD01M,

rose to almost 5.6% on Tuesday, while the 3-month yield

TMUBMUSD03M,

was 5.3%, according to FactSet. Bill maturing around the “X-date,” which could come as soon as June 1, have even higher yields.

Read: Debt-ceiling angst sends Treasury bill yields toward 6%

“Those are obviously pretty heady yields,” Catrambone said. “But it also exemplifies the market having to price in potential market disruptions in the month of June,” even though his team, like many in financial markets, expect that eventually “cooler heads will prevail” in Washington as the debt-ceiling standoff heads down to the wire.

How the money ran out

The Treasury in January hit its borrowing limit and began operating under “extraordinary measures” to avoid a default.

Cash balances at the Treasury Department have since dwindled to less than $100 billion, according to economists at Jefferies. Barclays strategists estimate its cash balance may fall below $50 billion between June 5-15.

“Basically, we are just draining our cash account to fund operations while we wait to figure out the debt ceiling,” said Lindsay Rosner, senior portfolio manager at PGIM Fixed Income.

But when the battle over the debt limit ends in a resolution, she expects longer-dated Treasury yields to increase, as haven buying on fears of potentially a full U.S. government default and a credit rating downgrade will have been taken off the table.

“The Armageddon, whatever small probability people were pricing in of catastrophe, remove that,” she said. “And that means the worst economic outcome has been removed.”

That’s also a reason why Rosner has been avoiding ultrashort Treasurys in the eye of the debt-ceiling fight in favor of 2, 3 or 4-year bonds offering some of the highest yields in years.

“We’re being afforded good yield, good spread, a couple of years out the curve,” she said. “Play that game.”

[ad_2]

Source link