[ad_1]

Patrice E. Jones likes to say her family got its 40 acres — the amount of land promised, then denied, to formerly enslaved people in the U.S. government’s only real attempt at reparations for centuries of treating Black people as property.

It was her ancestors’ stretch of farmland in rural Hazlehurst, Miss., purchased by her great-great-grandparents in the 1880s, that helped carry a family born into slavery up from more humble cotton-farming beginnings to college and trade-school education within a generation.

Jones’s great-grandfather, Rev. William Talbot Handy, born on the forested property only three decades after the end of the Civil War, even joined the Tuskegee Quartet and sang at Booker T. Washington’s funeral, Jones said. That was while Handy was paying his way through the Tuskegee Institute, the school Washington founded, with the labor and skills he’d earned from working the land in Copiah County, Miss., where more than half of the population had been enslaved in 1860, Jones said.

His own children, raised in New Orleans, included Dr. Geneva Handy Southall, the first woman to get a doctorate degree in piano performance, and D. Antoinette Handy, a flutist who — after studying at the New England Conservatory of Music, the Northwestern University School of Music and the Paris Conservatoire — joined the Richmond Symphony and directed the National Endowment for the Arts’ music program. Their siblings, children and grandchildren became activists, tradespeople, academics and artists.

That’s a credit to the power of landownership, Jones said. It’s why she’s reclaiming the property her family abandoned decades ago in an effort to return it to its former glory and to show what Black families might have had — and could still.

“I don’t think I’d be alive, had we not had that land to set foot on right out of slavery,” Jones, a 35-year-old influencer, content creator and educator at the University of New Orleans, told MarketWatch. “My ancestors who got the land at first were both born enslaved people, and they were able to use that land to farm cotton, have many children, support themselves, and try their best to catch up financially.”

Still, it’s no surprise that Jones’s family, the Handys, left behind the expanse of acreage to which they owed their initial successes. While the Handys had a legacy worth protecting in Hazlehurst, moving North or to more urban areas of the South during the Great Migration often meant better job and educational opportunities, as well as the hope of escaping racial violence, for many Black rural families.

Yet the Handys, who were hardly the only Southern Black landowners and farmers of that era, were among the few who managed to retain the rights to their land long after spreading out across the country.

Although hundreds of thousands of Black people acquired property in the decades immediately following the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War — despite the fact that white people were often unwilling to sell it to them at a fair price — that ownership largely dwindled over the next century. Discriminatory lending practices cut Black farmers off from capital, which contributed to foreclosures and tax sales; people involuntarily lost inherited property through partition sales and clouded titles, often stemming from the lack of access to estate planning that made Black families so vulnerable; the government seized property via eminent domain; and some Black households were forced to abandon property in the face of violence and intimidation.

In 1910, Black people operated and owned more than 2.2 million acres of farmland in Mississippi, according to government data — still a sliver of the 18.6 million acres farmed by owners, managers and tenant farmers statewide. By 2017, though, fewer than 400,000 acres of the 10.4 million acres of farmland in the state were owned by Black farmers.

Altogether, between 1920 and 1997, Black farmers in the U.S. lost almost all their land, worth roughly $326 billion in today’s dollars by one estimate.

“‘This is an example of what would have happened if we had received our 40 acres from the beginning. We received it. Look what has happened to our family as a result of landownership.’”

“As a Black person, so many of us are so disconnected from our family, where we come from — our roots — because of slavery, because of the Great Migration, because of violence, because of people being shot, and killed, and murdered,” Jones said. “To be a Black person in 2023, to be able to go back to this land, and be like, ‘There’s 400 acres of land over here that I come from, that I know my history of, that I know my roots, that I have cousins I can talk to and can tell me stories’ — that’s incredible. It gives me such a sense of pride and grounding and power. I feel powerful.”

As the federal government weighs potential pathways toward addressing a massive and persistent racial wealth gap — H.R. 40, the House bill to study reparations that’s been repeatedly reintroduced, gets its name from the 40-acre promise — Jones and her family members want policymakers to consider what Black families like the Handys gained largely by having access to property, and the ability to maintain it today.

Tisch Jones on the land in Hazlehurst.

Patrice E. Jones

“We have a whole history of ministers, teachers, artists, entrepreneurs,” said Tisch Jones, Jones’s mother, a professor emerita in the University of Iowa’s Theatre Arts Department and a civil-rights activist. “This land allowed that to happen, which is why I fight for reparations so much. This is an example of what would have happened if we had received our 40 acres from the beginning. We received it. Look what has happened to our family as a result of landownership.”

‘I owe my life to this land’

Jones began to have vivid dreams of the Hazlehurst land right before the pandemic’s onset, and started regularly driving the two hours from her New Orleans home to the family property as the U.S. economy shut down. The land’s peacefulness and forests, accompanied by the four houses her ancestors built, drew her in, and she was enticed by the idea of growing her own food. But the property had been vacant for years, and the homes were falling apart.

Nonetheless, “I fell in love,” Jones said. “I realized if I didn’t do something, nobody would. I just kind of felt like it was my calling.”

“‘Patrice is a steward of the land, and she wants to use that land to give others the vision of being stewards of their own.’”

Later in 2020, a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man, spurring dialogue about reparations and racial equity across the country. Jones’s family’s ancestral land felt crucial to a greater understanding of what Black people were owed, and her mother made the move from Minneapolis down to New Orleans to help see Jones’s work through.

“As a child, I didn’t understand the importance of the land,” Tisch Jones said. “I didn’t realize until I got to be older and started learning more about my history, and the history of my most direct family … what a beautiful gift we had.”

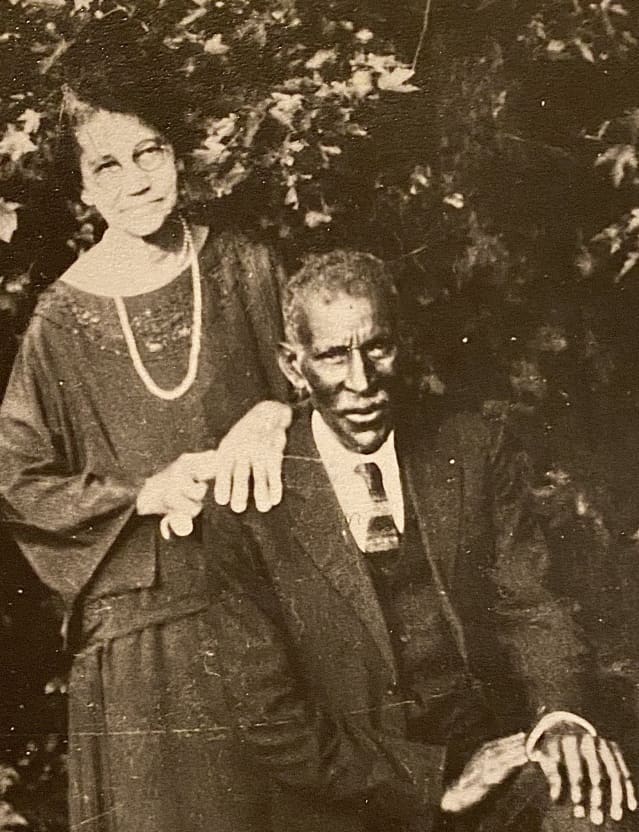

Patrice Jones’s great-grandfather, Rev. William Talbot Handy, had documented the land’s history in an autobiography, and she has known almost her entire life that the land, her lineage and her lighter skin were the byproduct of both slave-owning and enslaved ancestors: Jones’s great-great-grandmother and Rev. William Talbot Handy’s mother, Florence Geneva Handy, was born to an enslaved woman and the son of the man who owned her, Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Ephraim Peyton Sr., Jones said. Florence’s father, a white man, helped her purchase the property after she married the Handy family’s namesake, Emanuel Handy Jr., at 19.

Florence and Emanuel Handy Jr.

Patrice E. Jones

But Jones has also known that with the help of that land, her ancestors were able to have security that other Black families weren’t allowed.

The reverend’s wife, Dorothy Pauline Pleasant Handy, perhaps further recognizing the importance of what her family had created, also set up a trust in the 1970s to help maintain the land’s upkeep. The trust was eventually passed down through generations of women in the family; in 2020, Jones endeavored to become a trustee, a role she now shares with two other family members. (The title for the land itself is not in that trust but, importantly, is not in dispute either.)

Since then, she has been working on a revival of sorts, starting with her great-grandparents’ house, the largest of four structures on the property and where the reverend and his wife had intended to retire prior to their deaths. So far, that’s meant gutting and releveling the home, while also adding a new roof, new electricity, a new HVAC system and new drywall.

The other craftsman-style homes, built in the early 1900s and described by Jones as “teeny,” were used by three of her great-uncles, who remained on the land and farmed until the mid-’80s, when the final son of Florence Geneva Handy and Emanuel Handy Jr. died.

“They’re not falling — yet,” Jones said of the homes. “I’ve been doing everything I can to mothball them.”

All the while, she has documented the restoration process on TikTok and Instagram

META,

garnering millions of views on videos showcasing the property’s history, as well as her joy associated with it. In many of the clips, she’s dancing. Sometimes she breaks down her family’s ancestry, too, drawing upon scores of audio records, photos, newspaper clippings and government records to share fun facts — “My great-grandfather was a minister, and in 1932, Albert Einstein visited his church,” she says in one TikTok — as well as somber ones, like how her great-great-grandmother was listed as her own white father’s “servant” on the 1880 census.

“I owe my life to this land,” Jones says in one July 2021 TikTok video post with 3 million views. “Black land matters.”

Some of the comments on her videos praise the beauty of generational wealth in Black families, or say they hope to accomplish the same kind of revival with their own family’s property.

Still, restoring the homes is a difficult and expensive undertaking: Jones set up a GoFundMe campaign in early 2022 to raise $60,000, but has raised only a quarter of that goal. Adrienne E. Mason, a family member whom Jones described as “my fairy godmother,” also supported the project, contributing about $60,000 in belongings, funds and a gazebo before her death in February. Mason, who was older and Black, had lost the family farm where she grew up and found Black landownership immensely important, in addition to caring for the arts, Jones said.

Jones has also tapped her personal savings and money left in the trust by her great-grandmother, which together totaled approximately $60,000.

Jones’s brother, Patrick Rhone, a 55-year-old writer based in St. Paul, Minn., has experience restoring properties — he owns four homes with his wife — and knows what Jones is in for. But her work is well worth it to preserve the stories the family would like to tell future generations, he said.

“This isn’t about ownership; this is about stewardship,” Rhone said. “Patrice is a steward of the land, and she wants to use that land to give others the vision of being stewards of their own.”

Jones hopes to eventually turn the entire property into a healing space for artists and writers of color who need a place to work, rest and connect with their own histories and relationships to land. Jones’s great-grandparents’ home would be the retreat’s main office, kitchen and gathering space, Jones said, while she would split time between New Orleans and Hazlehurst.

“I believe all Black people need land access, because we worked the land in this country and built the economy we have today,” Jones said. “We need this space. We need the space to rest, we need the space to grow, we need the place to learn. We need a safe space.”

A time of peak Black landownership, and racial terror

Jones’s ancestors tended to the land in Hazlehurst during what wound up being a banner time for Black landownership in the U.S., despite the fact that a promise to give property to formerly enslaved people went unfulfilled.

As the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, Union General William T. Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton met with Black faith leaders and formerly enslaved people in Savannah, Ga., to discuss what newly freed enslaved people needed to be self-reliant. At that meeting, Rev. Garrison Frazier, an ordained Baptist minister who had purchased freedom for himself and his wife only eight years before the gathering, made the case for landownership, according to transcripts.

For a brief time, it looked like Frazier may get his wish. Days after the Savannah gathering, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which declared that 400,000 acres would be redistributed from Confederate landowners to formerly enslaved Black people at 40 acres each.

Whether that ownership would be exclusive, earned over time or merely temporary was unclear, said Thomas W. Mitchell, a professor and director for the Initiative on Land, Housing and Property Rights at Boston College Law School. But it was nonetheless seen as a firm promise by recently freed enslaved people, who were not deterred from landownership even after then-president Andrew Johnson reneged on the short-lived commitment to 40 acres.

Black Americans took on multiple jobs, pooled resources, requested the ability to purchase land from their former enslavers, and resisted eviction from occupied lands until they had acquired some 16 million acres of farmland by 1910, only 50 years after the end of the Civil War and the demise of reparations.

“We were still living in a society, certainly in the South, where its primary economic engine was agriculture,” Mitchell said. “If you were going to have any chance to have any kind of development socially and economically in our country, it was almost a prerequisite that you become a landowner — and in the South, a landowner of farmland.”

One of the newly minted Black landowners was Jones’s great-great-grandmother, Florence Geneva Handy, who was acknowledged as the child of her white father, Ephraim Peyton Jr., and raised partially in his home. Her mother and grandmother, whom Peyton Jr.’s father once enslaved, continued to work for the family after emancipation, Jones said.

After Handy married Emanuel Handy Jr., she received her father’s help in buying 40 acres of land. It’s unclear whether the amount of acreage was intentional; Jones believes that because the sale still occurred in the Reconstruction era, Florence and Emanuel may have searched for that size based on the initial promise of 40 acres to freed enslaved people. Either way, the couple grew the property to 116 acres in time and raised nine sons and two daughters there, using money from their crops to ensure each of their children had a trade-school education or college degree.

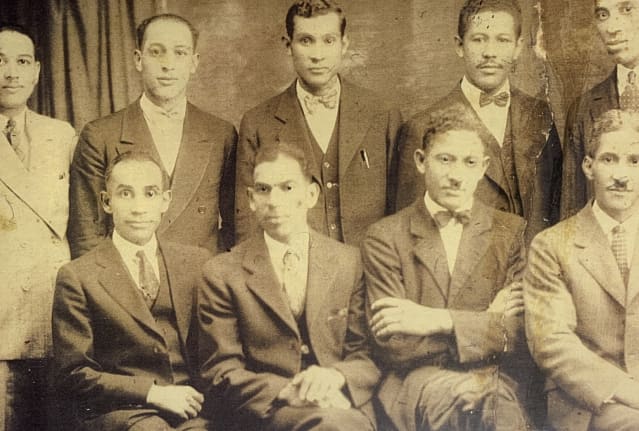

The Handy brothers.

Patrice E. Jones

“By the end of this, we had a mortician; we had a minister, who is my great-grandfather; we had Uncle Lon, who built the houses; we had a plumber, that was Uncle Dewey; the two girls became teachers, so we had somebody who could educate people,” Jones said. “Then they married people who could bring something back to the land — Uncle Lon married Aunt T.J., who was a midwife, so we could now birth babies.”

That was around the peak of Black landownership in the U.S., and a time in which the white-Black wealth gap was actually narrowing. The white-to-Black per-capita wealth ratio was 56 to 1 in 1860 and eventually declined to 9 to 1 in 1930, before the gap ultimately stagnated and even widened after the 1980s, according to a 2022 paper by Ellora Derenoncourt at Princeton University and the University of Bonn’s Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn and Moritz Schularick.

It was also a period marked by racial terror, Mitchell said, as Black landowners were targeted for white violence. For example, Anthony Crawford, a Black farmer who owned 427 acres of land, was beaten, stabbed, shot and hung by white people in Abbeville, S.C., in 1916 after an alleged dispute with a white merchant over the price of cottonseed, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, which has documented thousands of lynchings.

“You had a number of families who, just for basic survival, uprooted and left oftentimes a successful farm operation — because the more successful it was, the more they were in the crosshairs,” Mitchell said. “They basically abandoned their properties for self-preservation.”

Eventually, all but four of the 11 Handy children left Hazlehurst, Jones said, relocating to Chicago or other parts of the country. But they always knew the land was there for them if they needed it.

“‘A lot of families lose that connection, lose that history, lose that legacy when they lose the land — because we know that land has value, and they’re not making any more land.’”

The fact that the family was able to hold on to the property while many other members relocated was a “miracle,” thanks in large part to the trust established by Jones’s great-grandmother Dorothy, Jones said.

“She was savvy with money,” Jones said of Dorothy. “She bought these certificates of deposit so many years ago, and they wound up being some $30,000 total by the time I cashed them out. An incredible woman; one of my greatest inspirations and idols.”

Black-owned property in the South is often not protected by a will or another legal instrument, so when an owner dies, the land is passed down informally to following generations without a clear title, and ownership becomes unstable; such family land, known as heirs’ property, has become a key driver of Black land loss. Real-estate speculators can “pick off one family member, and then go to the local courthouse, file a lawsuit, and ask for the forced sale of the entire property,” said Mitchell.

“One of the racial gaps in this country that is least well-known, but not surprising when you think about it, is that there’s a massive racial estate-planning gap,” Mitchell said.

Historically, many Black farming households have been skeptical of the legal system because it’s so rarely served them, said Andrea’ Barnes, the director of the Heirs’ Property Campaign at the Mississippi Center for Justice, which provides families in the state legal assistance so they can keep, protect and utilize ancestral land. They also often lacked money to pay an attorney to set up their estate, or access to an attorney willing to work with Black people.

“When people aren’t able to hold on to the land and use the land, they lose the ability to have an economic benefit,” Barnes said, whether that be through farming the property, leasing it, selling off timber rights or profiting in other ways. “With heirs’ property, it’s vulnerable.”

Barnes recalled that even her grandfather, a farmer who died in 2019 at 91 years old, saw landownership as a means to end intergenerational poverty. It was a point of pride to leave that property behind for his family. But he was skeptical of estate planning, even as his granddaughter became an attorney.

While Barnes wasn’t able to convince him to establish a will, he did partition the property so it could be passed down to his children, along with his legacy.

“He was very vocal about the importance of land and maintaining that land in the family,” Barnes said. “A lot of families lose that connection, lose that history, lose that legacy when they lose the land — because we know that land has value, and they’re not making any more land.”

‘We’ve got something that is ours’

As the already-small population of Black landowners declines further, there are fewer of them to share their stories of success, and fewer examples of what generations of property ownership would have meant to marginalized families. Jones believes that Handy Heights is part of the Black history that needs to be told for generations to come.

There’s a lot Patrice says she still doesn’t know, like what it was like for her great-great-grandmother to be raised alongside the white family that enslaved her own mother, and to rely on that family for help securing her own economic freedom. But she knows that property ownership is precious; stewarding the land has even allowed her the ability to meet family members in Hazlehurst she’d never gotten to know.

Her 74-year-old mother, Tisch Jones, is proud that her daughter is devoted to sharing that legacy. She had herself once hoped to preserve the land and open it up as a space for the arts, and said it’s “very heartwarming” to see that dream continued.

“As long as that land is there, and all that forest behind the land, we are extremely rich,” Tisch Jones said. “We’ve got something that is ours.”

[ad_2]

Source link