[ad_1]

The U.S. economy relies on unpaid care to function, as parents juggle childcare and chores, and others manage elderly at home. Yet caregiving is not considered as part of economic output.

Here’s why economists say unpaid care is important, and contributes to GDP: Taking care of children or the elderly allows the rest of the population to work. But only paid care is considered as valuable, and counts towards economic output.

That omission misses a key fact about how society functions, academics argue, and is also the subject of a forthcoming paper.

When Jessica Morrison was working as a nanny ten years ago, she thought that motherhood would come easy.

“I was so cocky going into being a mother,” the 38-year-old recalled in an interview with MarketWatch. “But nobody warns you about what it’s like when they’re yours. She added, “You have to constantly talk yourself out of mom guilt.”

The mom of two, who works full-time in Philadelphia, Pa., said that even after her family’s schedule normalized to an extent after the coronavirus pandemic, it was still chaotic trying to manage work and her kids, aged 4 and 8.

“As soon as I walk in the door, it’s dinner, homework, baths, and then bed,” Morrison said. “But I feel guilty, because we don’t get to spend a whole lot of time, to just play, and be together, and talk about our day.”

“We’re all just running around trying to make ends meet,” she added.

Jessica Morrison and her family. She said unpaid care is largely regarded as invisible work.

(Photo: Jessica Morrison)

The “mom guilt” Morrison describes, she said, is due to her inability to split herself between what is effectively two full-time jobs — between being a mother and managing a career as a case worker working in social services.

Morrison, who is also a member of MomsRising, an advocacy group, felt like her job as a full-time mother went unseen.

She’s not wrong: Like millions of working women, her role is undocumented and unaccounted for by official government statistics.

Measurements of U.S. economic growth don’t include parenting or at-home caregiving as contributors to economic activity.

Adults in America with kids under the age of 6 spend an average of 2.2 hours a day on childcare, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). And about 14% of the population that’s over 15 provided unpaid care for the elderly — with a quarter of that group doing so daily.

But one academic argues that undervalues caregiving and the importance it has for society.

Even after the exhausting days and nights during the pandemic lockdowns, when parents had to manage both childcare and work, official data still only account for the value people produce at their full-time jobs, Misty Heggeness, a professor at the University of Kansas, told MarketWatch.

She called unpaid care work the “invisible work” that underlies the economy.

“You have women essentially working two jobs, which is the state of affairs where we’re at today, because even though men are being more active in household chores, it’s still women who are predominantly doing the majority of unpaid domestic work,” Heggeness said.

“I’m really concerned about the health and well-being of women today,” she added. “In our society, we still are not good at capturing and recognizing all of the diverse economic activity that women engage in not only out in the labor force, but also within their homes.”

Heggeness has been researching how the field of economics could factor in unpaid care work as a component of economic activity.

Her paper is set to appear in the American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings in May.

How we measure ‘economic activity’

Not only is unpaid caregiving not included in official statistics, in some ways, the country’s measure of economic activity considers it as a variable that pulls people out of the workforce.

For instance, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, there was a 3% drop in labor-force participation, according to a U.S. Chamber of Commerce report. Many parents, especially mothers, had to step back from their careers as childcare centers across the nation shuttered.

Between December 2019 and March 2021, nearly 9,000 childcare centers in 37 states closed, according to a report by Child Care Aware. Nearly 7,000 licensed family child-care programs, or home-based care centers, in 36 states shut down.

Two years later, while men have mostly returned to work, women’s labor force participation is still lower than pre-pandemic levels. In other words, one million women are still “missing” from the workforce, the Chamber of Commerce report stated.

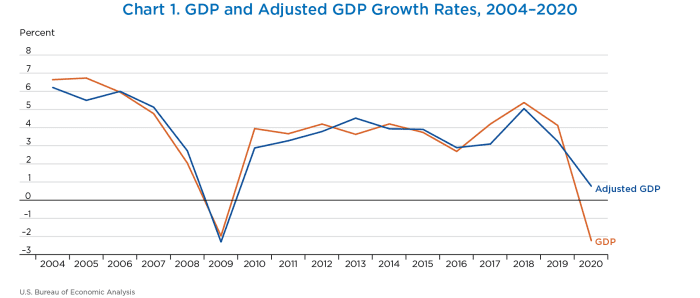

Economists have attempted to factor in the value of “household production.” In this chart (below) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, economists quantify the value of production, which closely tracks overall GDP. The difference between the orange and the blue lines in 2020 show how U.S. GDP is higher when accounting for unpaid caregiving.

Chart 1 shows growth rate of nominal GDP and adjusted GDP (GDP plus household production) from 2004 to 2020.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

At the onset of COVID-19, pandemic-induced lockdowns created “a sharp decline in market activity,” the economists said. But household production still held up the overall GDP number — because work didn’t stop at home. Household production refers to cooking, cleaning, watching the kids, etc.

For families like Morrison’s, the pandemic had a silver lining, at least at first. “I was really lucky to be able to work from home,” she said. But it quickly turned. “It kind of blurred the lines between work and home,” Morrison said. “I would be in the middle of doing something for work and I would be called in to take care of something with my children, or something home-related.”

According to OxFam International, women and girls contribute at least $10.8 trillion annually to the global economy, by putting in 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work daily.

Getty Images

Heggeness, who has spent years in the federal government working with statistics, argues that measures of “jobs” that are counted as economic activity (such as GDP) need to consider work done in the house.

Overlooking the value of economic activity that takes place within the home is the result of bias due to the field of economics being predominantly male, she argued. The “girly” statistics of economic activity inside the home are significant, she stressed, adding: “As a profession, we take unpaid care work as a given.”

For instance, Heggeness said, in the U.S., women aged 16 and older spend 8.6 hours a day in both paid and unpaid labor. In comparison, men spend 8.3 hours a day.

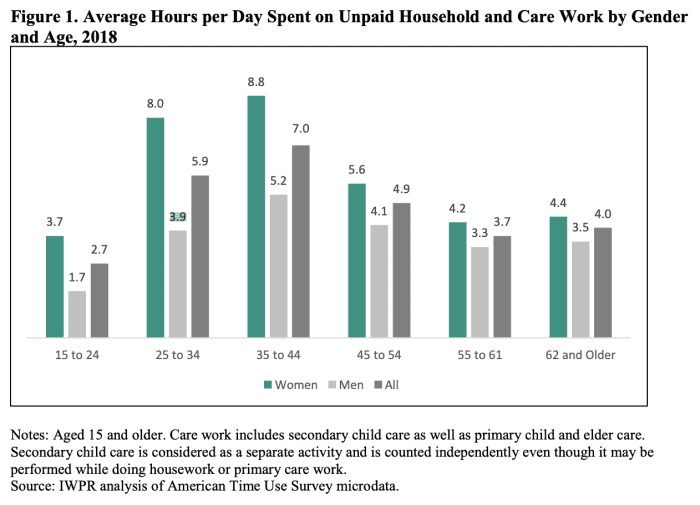

Among those who work full-time, women spend an average of 4.9 hours per day on unpaid household and care work, according to a paper by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Men only spent 3.8 hours on the same — a full hour less per day. Heggeness cited the study and extrapolated that to add up to 249 hours in 2023 — or 31 extra days of work per year.

Analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata.

Chart: Institute for Women’s Policy Research

She also notes that according to OxFam International, women and girls contribute at least $10.8 trillion annually to the global economy, by putting in 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work daily.

“The fact that women are, on average, more economically active than men is a sobering girly statistic, and one not captured in our core traditional economic statistics on the economy,” Heggeness said.

Unlike the value of goods produced outside of the home, which is admittedly easier to quantify, trying to produce statistics on unpaid care work is “challenging,” she concedes. But it’s not impossible.

On an average day, a mom of kids below 6 spent 1.2 hours providing physical care, like bathing or feeding a child.

Getty Images

Measuring unpaid care work

In fact, the federal government already is measuring unpaid care work.

For instance, the annual American Time Use survey, published last in June 2022, offers some methods of quantifying unpaid care work, particularly the care of children.

Adults living in homes with kids under the age of 6 spent “an average of 2.2 hours per day providing primary care” for them, the survey said. Primary care refers to tasks like physical care such as bathing or feeding a child, or actively engaging the child such as by reading to them.

Between men and women, the difference was stark: On an average day, a mom of kids below 6 spent 1.2 hours providing physical care. Men spent 31 minutes.

Heggeness said economic measures could broadly break caregiving down to the following: Time spent directly engaging the child, time spent supervising your child, and time spent on domestic chores.

The invisible exhaustion of parenting

If and when unpaid care work is included as economic output, on par with paid work, that will reveal how many working parents — particularly mothers — are pulling off double duty.

Workers who also take on unpaid care work feel a “level of exhaustion” by working double time at home and in the office. But only one of those two jobs is recognized by official stats, Heggeness said.

“We cannot measure how increasingly overworked and exhausted our care workers might be,” Heggeness wrote, “if we continuously ignore unpaid care work done within homes … [by] individuals who also engage in paid work outside of their home.”

When children fall ill and stay at home, many parents have to juggle their work and care for them simultaneously.

Getty Images

Picture a scenario where children fall sick, and have to stay at home to prevent the illness from spreading to other children in school. The burden of childcare and full-time work collides for working parents.

As of last September, Morrison calculated that her daughter missed over two weeks of school since she’s been back in the classroom, Morrison said. “Oftentimes, when she gets sick, she misses two to three days at a time. And she’s been constantly sick. So that has been really rough.”

That requires Morrison and her husband to scale back on work. She said part of her family’s finances have taken a hit as a result. The couple has fallen behind on every single monthly mortgage payment since July.

“As far as childcare goes, we simply can’t afford it,” Morrison added. Her husband, who is self-employed, has been handling the kids since she has to go into the office on weekdays.

“We’ve had to do a lot of juggling,” she said. “It’s stressful.”

How much would the former nanny pay today, for childcare, if money wasn’t an issue?

“When I was a nanny 10 to 15 years ago, I was making $14 an hour,” she said. “At this point, I would pay them at least $20 to $25.”

She added, “It’s a hard job.”

[ad_2]

Source link