[ad_1]

Financial conditions are now looser than in September, says economist

Financial conditions in the U.S. are looser than in September, says economist.

Getty Images

The feel-good tone gripping markets in the home stretch of 2023 may not be what the Federal Reserve had penciled in for the holidays.

The stock market in December, once again, has been knocking on the door of record levels, driven by optimism about easing inflation and potential Fed rate cuts next year.

But while the prospect of double-digit equity gains this year would be a reprieve for investors after a brutal 2022, the latest rally also points to looser financial conditions.

Ultimately, the risk of looser financial conditions is that they could backfire, particularly if they rub against the Fed’s own goal of keeping credit restrictive until inflation has been decisively tamed.

Read: Inflation is falling but interest rates will be higher for longer. Way longer.

Specifically, the November rally for the S&P 500 index

SPX

can be traced to the 10-year Treasury yield

BX:TMUBMUSD10Y

dropping to 4.1% on Thursday from a 16-year peak of 5% in October.

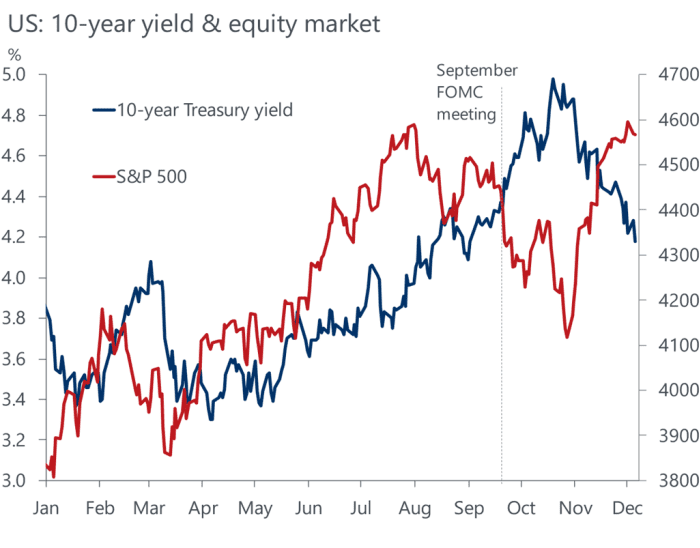

Falling 10-year Treasury yields from a 5% peak in October coincides with a sharp rally in the S&P 500 at the tail end of 2023.

Oxford Economics

The Fed only exerts direct control over short-term rates, but 10-year and 30-year Treasury yields

BX:TMUBMUSD30Y

are important because they are a peg for pricing auto loans, corporate debt and mortgages.

That makes long-term rates matter a lot to investors in stocks, bonds and other assets, since higher rates can lead to rising defaults, but also can crimp corporate earnings, growth and the U.S. economy.

Michael Pearce, lead U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, thinks the November rally may put Fed officials in a difficult spot ahead of next week’s Dec. 12 to 13 Federal Open Market Committee meeting — the eighth and final policy gathering of 2023.

“The decline in yields and surge in equity prices more than fully unwinds the tightening in conditions seen since the September FOMC meeting,” Pearce said in a Thursday client note.

The Fed next week isn’t expected to raise rates, but instead opt to keep its benchmark rate steady at a 22-year high in a 5.25% to 5.5% range, which was set in July. The hope is that higher rates will keep bringing inflation down to the central bank’s 2% annual target.

Ahead of the Fed’s July meeting, stocks were extending a spring rally into summer, largely driven by shares of six meg-cap technology companies and AI optimism.

Rates in September were kept unchanged, but central bankers also drove home a “higher for longer” message at that meeting, by penciling in only two rate cuts in 2024, instead of four earlier. That spooked markets and triggered a string of monthly losses in stocks.

Pearce said he expects the Fed next week to “push back against the idea that rate cuts could come onto the agenda anytime soon,” but also to “err on the side of leaving rates high for too long.”

That might mean the first rate cut comes in September, he said, later than market odds of a 52.8% chance of the first cut in March, as reflected by Thursday by the CME FedWatch Tool.

Stocks were higher Thursday, poised to snap a three-session drop. A day earlier, the S&P 500 closed 5.2% off its record high set nearly two years ago, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA

was 2% away from its record close and the Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP

was almost 12% below its November 2021 record, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

Related: What investors can expect in 2024 after a 2-year battle with the bond market

[ad_2]

Source link