[ad_1]

We have just published a brief on a really interesting paper by Natee Amornsiripanitch, a senior financial economist at the Philadelphia Fed, that explores the relationship between age and the probability of being denied a mortgage application. The paper uses Confidential Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data, which contain applicant and co-applicant age and a rich set of applicant, property, and loan characteristics.

The analysis focuses on a subset of mortgage applications — namely, rate-and-term refinance applications that are associated with a single borrower. The focus on single-borrower stems from the need to know the borrower’s age, which is unclear with two borrowers. The focus on refinance applications is to control for being a homeowner, because homeowners tend to have more financial resources and longer credit histories than renters.

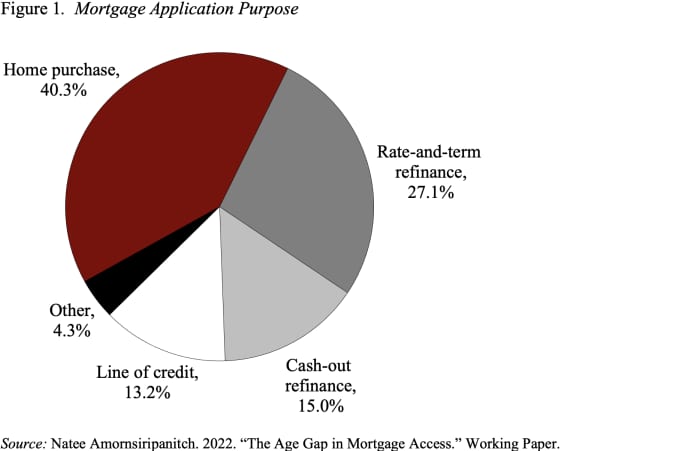

The final sample contains approximately five million refinance applications, which make up 27% of total mortgage applications (see Figure 1); and borrowers who are older than age 50 account for about 40% of the rate-and-term refinance applications.

Natee estimates an equation that relates rejection to applicants’ age, controlling for a host of applicant/loan/property characteristics, census tract, and lender. This specification makes it possible to estimate the conditional correlation between applicant’s age and mortgage application outcomes among individuals who applied for rate-and-term refinance loans under very similar circumstances.

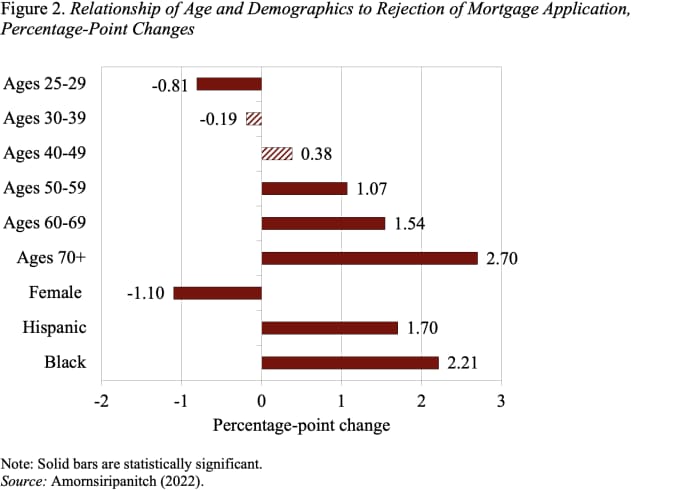

The results reveal several patterns (see Figure 2). First, the relationship between applicant age and probability of rejection increases monotonically with age.

Second, the economic magnitude of these coefficients is large, given that the average rejection rate is 17.5%.

Third, relative to race and ethnicity, applicant age is an equally important correlate of mortgage approval.

Finally, the coefficient for female applicants is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that the probability of rejection is lower for women.

The results are robust. As noted, the findings are not driven by older individuals applying for mortgages with more stringent lenders. Excluding 2020 applications produces the same pattern, which means the results are not driven by COVID-19. Omitting age groups from the equation does not affect the coefficients on the other variables. Separate estimates for government guaranteed loans produce the same qualitative results. Finally, the pattern is also evident for cash-out refinance applications.

Why is this happening?

The most relevant reason for rejection is “insufficient collateral,” which could occur either because older homeowners are unable to maintain the quality of their homes or they wish to consolidate multiple mortgages into one.

The need for more collateral could also occur if older borrowers were really riskier. One variable omitted from the equation — related to creditworthiness and age — is life expectancy or age-related mortality risk. Having a borrower die can be costly to the lender, because it increases the likelihood of the loan being paid off early (prepayment risk) or entering foreclosure (default and recovery risk). Indeed, several facts — discussed in the brief and paper — suggest that age-related mortality risk could be driving the correlations presented above.

Given that mortality risk has real economic implications for lenders means that the results of this study do not necessarily indicate that lenders are violating fair lending legislation. This caution is reinforced by the fact that regulations allow the consideration of a borrower’s age in credit decisions under some circumstances and that the results should be viewed as an association between age and rejection – not a causal relationship.

Regardless of the reason, however, it is important for older individuals to know that they are more likely to be denied credit.

[ad_2]

Source link