[ad_1]

What does a 3% 401(k) match mean to you? If you’re a little math-challenged—like most of us—it probably doesn’t mean much. It’s a number, just like all the other impossible numbers associated with retirement, that never seem to add up to enough.

Sometimes you need to take a step back and think about things a different way.

What if you think about money as time?

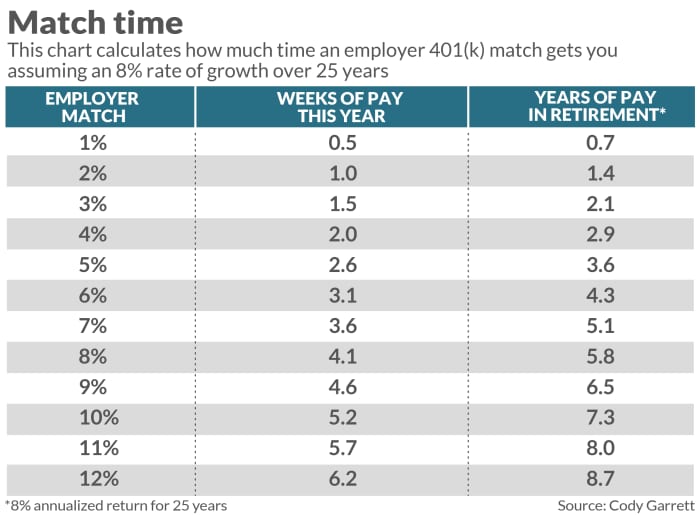

That can make a 401(k) match, which is when your company encourages you to contribute to your retirement account by adding money in proportion to yours, suddenly go from a nebulous concept about “free money” into two years of your precious time in retirement. Or you could think about it in current-day terms, which means that 3% match equals almost two weeks of your current pay.

Read: 4 burning questions you should ask about your 401(k)

Financial planner Cody Garrett used this visualization when he was explaining 401(k) plans to groups of employees and trying to convince them to contribute more—at least up to the company match. He wanted a way for them to really connect with the sums involved, rather than try to wrap their heads around percentages and apply it back to their current take-home pay. He worked it up into a chart that he now uses as part of the offerings for his financial education company Measure Twice Money.

Think about it this way: If you make $50,000, which is $961 per week, and you contribute 3% of your salary to your 401(k), that’s $1,500. If your company matches that, they add $1,500 to your account on top—almost two weeks of pay. If you invest that much each year for 25 years in an account that earns an average of 8% return over 25 years, you have just over $100,000 at that point, which is two years of your current salary. If you go up a notch to 4%, you save $2,000 a year and end up with more than $150,000 in your account, or roughly three years.

“A difference of 1% doesn’t sound like a big deal, but I’d say to people, if your employer offered you an additional week and a half of vacation would you take it?” says Garrett. “Of course, the employer match isn’t meant for the current year. It’s like your employer giving you vacation time in retirement. So a 3% match is equivalent to over two years of ‘vacation’ in retirement. Would you say no to that?”

Garrett’s formula assumes compounded investment growth at an 8% annualized return over 25 years, because he’s gearing this for long-term retirement savers. While that return might seem impossible at the moment, he says it still makes sense given historical market averages. The returns can be scaled to be more conservative, and the math works with any level of salary, assuming your retirement spend is proportional to your earnings. It also works with any level of 401(k) match. If you’re lucky enough to have a 6% match, that would buy you more than four years of retirement spending—but only if the employee is willing to put in that much.

Think about saving more

Employers offer many varieties of 401(k) matching scenarios. Some offer a straight percentage, some offer different portions for different thresholds. The most common, according to Vanguard’s How America Saves 2022 report, is 50 cents per dollar on the first 6% of pay, which is equivalent to a 3% match.

Employees can contribute up to $22,500 in 2023, with an extra $7,500 for those 50 and over. But most do not contribute up to that level. Despite auto-enrollment programs that have become widely used in the last several years, only two-thirds of participants even get their full employer match. And those who enroll via auto-enrollment are actually less likely to get the full match, according to Vanguard. But those who have auto-enrollment plus auto-escalation, meaning their participation gets increased automatically each year, actually end up saving more than the employer match after three years.

When Garrett developed his chart, he found that people responded to the time element, and thought seriously about contributing more. “It’s that extra nudge to think about what that time actually means,” he says. “People always say, ‘I wish I had more time with kids.’ It’s always about time, not about percentages. They never say, ‘I wish I would have taken 5% not 4%.’”

More from Beth Pinsker

[ad_2]

Source link