[ad_1]

The Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

closing above its 200-day moving average— as it has been doing for several trading days now — is not the bullish development that many on Wall Street believe it is.

That’s crucial information, because many investors look at an index closing above or below its 200-day moving average to signal that a major trend. If they’re right, then we are in a new bull market.

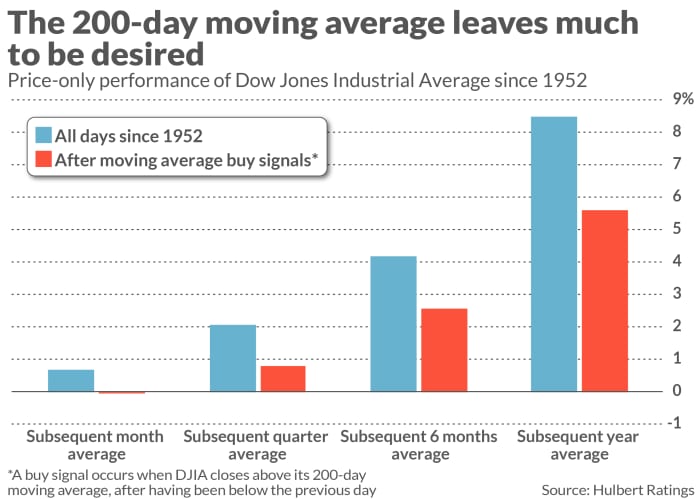

Yet a close analysis of the Dow over the past 70 years fails to support this. The Dow actually has tended to perform worse following days in which it moved from being below its 200-day moving average to closing above — a “buy” signal, in other words. This tendency is not strong enough to satisfy traditional standards of statistical significance. So it would be going too far to conclude that traders should sell on the basis of the Dow’s recent moving-average “buy” signal.

Still, there is no support for the notion that you should respond to the 200-day moving-average buy signal by increasing equity exposure. In short, this buy signal has little real world investment significance.

A good illustration of how the 200-day moving average comes up short is what happened this past August, when the Dow closed above its 200-day moving average for a couple of consecutive days. Far from signaling a powerful new uptrend, however, the Dow almost immediately turned down. A month later it was 15% lower.

This is just one data point, but the longer-term record is consistent with it. As you can see from the chart below, the Dow on average since 1952 has tended to do significantly worse following 200-day moving average buy signals. This is true over time horizons as short as one month and as long as one year.

Given these results, you might wonder how anyone could have concluded that the 200-day moving average was a reliable indicator of the market’s major trend. The answer appears to be that its long-ago record was a lot better than it has been over the past couple of decades.

The split between its decent track record and the dismal one occurred in the early 1990s. That was when broad-index exchange-traded funds first became available, making it easy for individual investors to trade into and out of the entire market with a single transaction. Until then, investors faced formidable barriers to frequent trading.

It’s not a coincidence that this is when the 200-day moving average became less effective, according to Blake LeBaron, a finance professor at Brandeis University. The Efficient Markets Hypothesis predicts that a market-timing strategy’s performance will deteriorate as more investors follow it. LeBaron has found that moving-average systems in other markets also took a turn for the worse in the early 1990s.

There is much irony in this. The 200-day moving average did a much better job identifying changes in the market’s major trend when it was difficult, if not impossible, to act on its signals in a timely fashion. And when it became easy to do so, it stopped doing as good of a job.

Tweaking the 200-day moving average

Devotees of the 200-day moving average have responded over the years by proposing a number of modifications in hopes of resurrecting it. But these modifications haven’t succeeded.

Consider research conducted in 2013 by Nate Vernon, currently an economist in the Fiscal Affairs Department at the International Monetary Fund, but who at the time of studying moving averages was an intern at my firm, the Hulbert Financial Digest.

Vernon explored three ways of potentially improving on simple moving-average systems: Allowing transactions only at month end, in order to reduce transaction frequency; employing exponential moving averages, which have the effect of more heavily weighting recent market action, and crossover strategies, which focus on the behavior of two different moving averages of different lookback lengths.

All three came up empty. Vernon’s conclusion: “Moving averages [even in their modified versions] leave a lot to be desired. Their real-world experience is far lower than what most investors assume.”

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Energy stocks are in a bubble — and here’s when they’re likely to crash

Also read: Home prices will fall in 2023, but affordability will be at its worst since 1985, research firm says

[ad_2]

Source link