[ad_1]

Like anyone else, I’ve made my share of financial mistakes, small and large. I’ve sold a house at the bottom of the real-estate market. I’ve bought exercise equipment I didn’t use. And I’ve spent way too much on lottery tickets.

But nothing quite frustrates me as much as the $300 I recently lost because I didn’t take note of an asterisk.

It all has to do with a bank promotion I signed up for that had various requirements, including a minimum-balance one. I thought I had followed everything to the letter, only to discover that by missing that asterisk — and the fine-print disclosures that said asterisk would have led me to — I had misunderstood the terms.

Perhaps what frustrated me is that while I could blame myself, I somehow felt I wasn’t fully at fault. Couldn’t the bank have foregone the fine print (and the asterisk) and just spelled out the terms of the promotion in nice big letters?

This wasn’t the first time I’ve been penalized for not paying heed to the fine print. It happened not that long ago with a credit-card offer — again, the relevant terms were lost in the land of small type. And I’m sure there are countless other instances from my past because, really, who reads this stuff?

Apparently, almost no one. A Deloitte survey from 2020 found that 80% of consumers don’t take the terms and conditions in certain documents seriously — meaning they “always,” “almost always” or “sometimes” accept them without reading them.

And there have been some hilarious experiments to prove how consumers are so casual — or clueless — when it comes to fine-print matters.

“‘In the modern day, we’ve got the attention span of crickets. The likelihood of reading 10 pages [of fine print] is slim to none.’”

My favorite example: Purple, a WiFi provider, once put a joke clause into its terms and conditions that said users of its service agreed to committing themselves to 1,000 hours of community service. Among those, ahem, services: cleaning toilets and picking up wads of chewing gum.

Apparently, 22,000 people unwittingly accepted the deal in return for getting online. Purple didn’t hold them to the commitment, since the point was to promote consumer awareness of how companies can trip you up and to illustrate how Purple was aiming to avoid that.

Purple CEO Gavin Wheeldon told me he sympathizes with those who skip the lengthy contractual documents since he counts himself among the legally bewildered.

“In the modern day, we’ve got the attention span of crickets,” he said. “The likelihood of reading 10 pages [of fine print] is slim to none.”

The result of not reading this stuff can be costly, as my $300 example attests. But I’m hardly alone.

On social media, you’ll find no shortage of folks complaining about how they were tripped up by the fine print. One choice Reddit thread, with a four-letter word in the title of the post, offers one case after another, relating to everything from product warranties to employment situations. Indeed, there are nearly 7,000 responses to the thread.

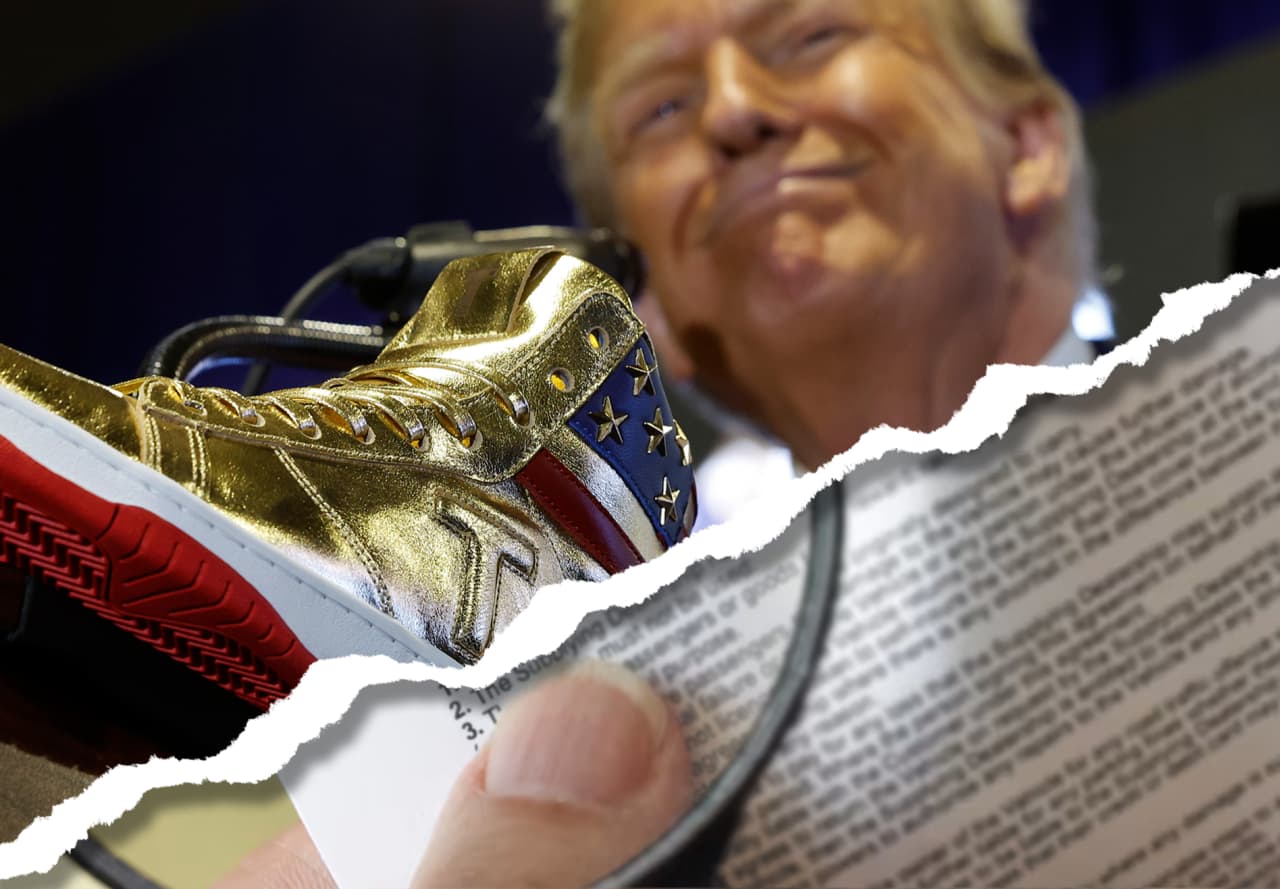

The fine-print concerns extend all the way to Donald Trump’s latest entrepreneurial venture — namely, his new line of sneakers, which are priced from $199 to $399. Questions have been raised as to when the shoes might show up at anyone’s door, since the fine print on the sneaker website says the projected ship dates are between June and August 2024. But even then there’s this caveat: “Shipping and delivery dates are estimates only and cannot be guaranteed. We are not liable for any delays in shipments.”

On X, the social-media platform, one commentator had the following to say in response: “Read the fine print. These things aren’t getting delivered anytime soon. If ever.”

A Trump spokesperson didn’t respond immediately to a request for comment.

Which is not to say companies are necessarily at fault for putting all this stuff in tiny letters, at least according to some legal experts. In a litigious society, businesses inevitably need to cover their bases, and that often translates into long legal documents rendered in 8-point (or under) type.

The intention is not necessarily to mislead the consumer, said Nicholas Creel, an assistant professor of business law at George College and State University. But he acknowledged that fine-print disclosures have “the potential to easily do so.”

To be clear, if there’s a line that’s crossed — that is, if the fine print seemingly turns into a fine deception — consumers could have some legal protection and a way to fight back.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an independent federal agency, notes that abusive conduct by companies is covered under the Consumer Financial Protection Act. Such conduct is defined, in part, as anything that “interferes with the ability of a consumer to understand a term or condition of a consumer financial product or service,” according to the CFPB.

And there are remedies beyond going the legal route. Consumers can always file a complaint with the Better Business Bureau, for example.

Still, maybe the best defense is a good offense. Namely, should we actually attempt to read all that fine print?

“‘It is important as a consumer to read the fine print, especially when it can mean getting money you’re entitled to.’”

Here’s where I got differing responses. Erika Kullberg, an attorney and personal-finance expert who has made something of a career explaining what’s hidden in all those terms and conditions, says you should put on those reading glasses.

“It is important as a consumer to read the fine print, especially when it can mean getting money you’re entitled to,” she told me.

But others, particularly attorneys I spoke with, pointed to a stark reality: We’re so bombarded with fine-print disclosures these days that we’d be spending hours every month, even every week, going through all of them. And in the end, for what? You have to weigh the value of your time versus the value of what you might stand to gain (or lose) financially.

Another option: You can hire an attorney to do all the reading for you. That might make little sense when it comes to, say, signing up for a $40-a-month gym membership, knowing that an attorney’s hourly rate can run hundreds of dollars. But when it comes to major purchases, such as a car or certainly a home, that’s another matter.

“It comes down to a cost benefit analysis,” said Justin Leto, an attorney and entrepreneur.

I’m fairly sure it wouldn’t have been worth my while to bring most of the fine-print documents I’ve glossed over — or, let’s be honest, ignored — to a lawyer. A case in point: I’d probably have ended up paying way more than the $300 I lost in that bank-bonus matter.

But I’d still argue that companies, even if they’re staying within the letter of the law, could do better with their disclosures. In many instances, it seems fairly obvious what key terms and conditions will matter most to consumers, so why can’t businesses make them abundantly clear?

Either that or they should at least provide everyone with a magnifying glass.

[ad_2]

Source link