[ad_1]

When does it make sense to invest in companies with specific characteristics instead of in a broad index like the S&P 500

SPX

?

Academics have long analyzed the relationship between stock returns and factors such as value, growth and size. Their research has at times revealed promising results.

More recent research has shown that investing based on three factors — size, value and profitability — can dramatically improve outcomes for those saving for retirement, as well as those living in retirement.

In fact, people who invest in those factors had more assets at retirement, a lower risk of depleting their savings, and larger bequests, according to a paper published by Mathieu Pellerin, a senior researcher and vice president at Dimensional Fund Advisors.

Emphasis on premiums increases initial retirement assets

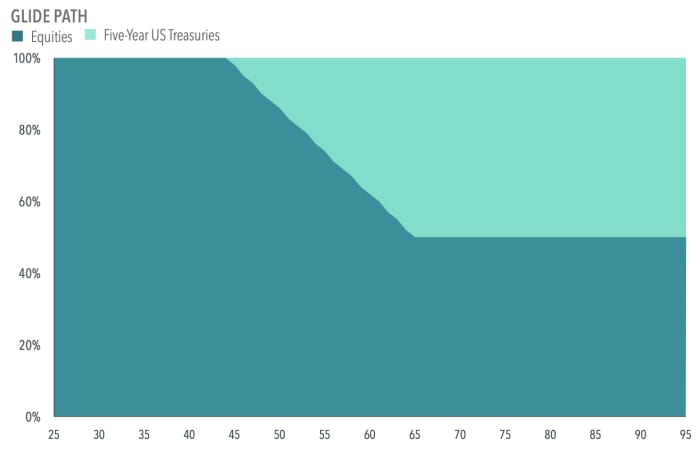

In his research, Pellerin looked at a hypothetical investor who starts saving at age 25, retires at 65, and dies at 95. The investor uses a glide path that starts with 100% equities at 25, starts transitioning toward fixed income (5-year U.S. Treasurys) at 45, and reaches an equity landing point of 50% at 65.

Mathieu Pellerin, Dimensional Fund Advisors

During the accumulation period, the investor makes equal monthly contributions of about $1,042 per month, for a total of $12,500 per year, or $500,000 from age 25 to 65. During the decumulation period, the investor spends according to the 4% rule.

To study the impact of pursuing the equity premiums, Pellerin used two equity indexes: the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) 1-10 index, a market-cap-weighted index that reflects the performance of the broad U.S. equity market, and the Dimensional U.S. Adjusted Market 1 index, an index that reflects the performance of an equity allocation with an integrated and balanced emphasis on size, value and profitability.

In essence, Pellerin sought to determine how much “lift” an investor gets by switching from a purely passive broad market index to an actively managed core portfolio.

What Pellerin found was that premium targeting increased the amount of money accumulated at retirement when studied using two different methods. Using historical data, premium targeting increased median assets by 22%, from $2.09 million to $2.55 million. And using simulations that assume that the real expected equity return is 5.0%, median assets rose 20%, from $1.07 million to $1.28 million.

Put another way, the broad market index rose 8.1% per year in Pellerin’s study, while the premium-targeting index rose 9.1% per year. The premium-targeting portfolio was slightly more volatile than the broad-market-index portfolio. “That extra average return over the long run can overcome the slightly higher volatility,” he said.

“These results are encouraging,” Pellerin wrote. “A portfolio that incorporates controlled, moderate premium exposure can strike a balance between higher expected returns than the market and the cost of slightly higher volatility and moderate tracking error.”

“Moreover, while the size, value and profitability premiums can each have sustained runs of underperformance, the probability that they jointly underperform is lower, and the probability that they jointly underperform over multiple decades is lower still,” he added. “As a result, targeting these long-term drivers of stock returns is likely to increase assets at the beginning of retirement.”

Failure rates in the decumulation phase

Pellerin also investigated the likelihood of a hypothetical investor depleting their assets prematurely when withdrawing 4% annually from a balanced portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds over 30 years.

For starters, Pellerin noted that the original 4% rule was engineered to have a 0% failure rate over rolling 30‑year historical periods. And in his study, using historical returns, the failure rate was 2.5% for the premium-targeting index versus 4.7% for the broad U.S. equity-market index. But the benefits were even larger using simulations that assume that the real expected equity return was 5%: a 12.9% failure rate for the premium-targeting index versus 19.9% for the broad market index, a reduction of 7 percentage points.

“There’s a more meaningful benefit if stock returns are lower going forward,” he said.

Bequests at the end of the decumulation phase

Pellerin also studied whether premium targeting could increase the size of a hypothetical 95-year-old investor’s bequest, which is money one leaves to someone after they die. For instance, using historical returns, the median bequest as a percentage of initial assets is 29.2 percentage points higher under premium targeting.

“So, you have [by investing in a premium-targeting index] the benefits to accumulating,” he said. “You can enter retirement with more assets. But even if you wake up at age 65 and you say, ‘Oh, this looks great, I want to try that,’ you still can benefit just by supporting your ongoing spending better, and also by potentially getting a higher expected bequest. … This is something that applies at all stages of life — whether you’re young and you want to accumulate faster, whether you want to support spending better, whether you want to maximize your chances of finding a high bequest, this is all good.”

The bottom line

“Core investing is beneficial for everyone, in my opinion,” Pellerin said. “But especially for retirees, when all the outcomes of relevance are over decades, really. You’re not trying to hug the gyrations of the S&P 500 last quarter. You’re trying to really make sure you have enough returns to meet your financial objectives. I think it’s a very attractive proposition there.”

“In fact, if you’re saving for or already living in retirement, there’s actionable advice to consider,” he added. “Instead of investing in an ETF or mutual fund that tracks the S&P 500 stock index, think about choosing a premium-targeting ETF or mutual fund. These focus on factors like size, profitability and value.”

Some examples of multifactor ETFs: Dimensional U.S. Equity

DFUS,

Pacer U.S. Cash Cows 100

COWZ,

Schwab Fundamental U.S. Large Company Index

FNDX,

Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta U.S. Large Cap Equity

GSLC

and VanEck Morningstar Wide Moat

MOAT.

Of course, you need to be able to suffer through some years of underperformance. “This isn’t free money,” he said. “There’s a certain risk. … But I think for most people, it’s going to be a pretty good trade-off.”

Still, if you adopt this approach, you will need to be honest with yourself and ask: What is the amount of underperformance you’d be willing to stomach?

[ad_2]

Source link